The Ties That Bind

15 Feb2011

By Judith Joseph | Tweet

Judaism is a religion/culture that wraps its fingers tightly around us. The imagery of Judaism is filled with tying, binding, encircling, making a fence, making a division. We are swaddled, tethered, offered a lifeline. We are encumbered with obligation. Marked by the ties that bind us. Our loins are girded. So, where do we find these ideas in the work of Jewish artists?

As a ketubah (decorated Jewish marriage contract) artist, I spend much of my time writing the words that tie a couple together religiously and socially. The words formed by threads of ink make a chain between two people. It seems that when I write Hebrew letters, they are like the straps of the tefillin (phylacteries) on skin.

- Calligraphy by Judith Joseph

- Banyan Tree Ketubah, egg tempera and india ink on paper, 2010, by Judith Joseph

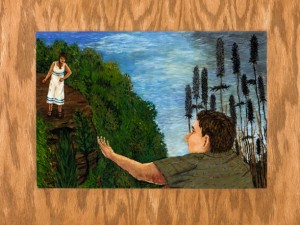

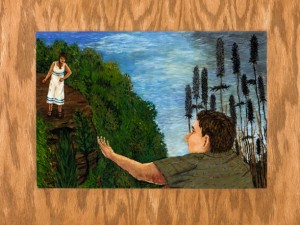

Gabriella Boros, an Israeli-born daughter of Holocaust survivors who resides in Chicago, creates paintings about the ties of history, memory, and relationships. On the surface, they are colorful and pleasant; beneath the skin, there is drama. Her painting, You Are Sanctified Unto Me, depicts the Jewish practice that binds man and woman together through a verbal statement before witnesses, with a vow sealed by the ketubah: marriage.

- You Are Sanctified Unto Me, acrylic on wood panel, by Gabriella Boros

Bert Menco, a Dutch-born artist who lives in Chicago, explores the desire to bond. He describes his work thus: “My images tend to deal with confined spaces containing certain characters that reach out to one another but do not quite succeed in meeting; hiding behind reality, masking yourself, or trying to show with the mask how you really feel. Maybe one’s “normal†face is really a mask?â€

- Dunce, oil on clayboard, by Bert Menco

- Bar Mitzvah Knot, charcoal on paper, by Sharon Goodman

Many of the Jewish things that physically bind are men’s things. As a girl, I watched my father tie on tefillin and admired the red marks that slowly faded on his skin after he removed the leather straps, a sort of kosher tattoo in invisible ink. It seems the message is meant to be internalized, not “worn on one’s sleeve.â€

My father enjoys “dichuning,†(making the special priestly blessing for the congregation) and as a Kohen (descendant of Temple priests), he is entitled to throw his tallit (prayer shawl) over his head on Yom Kippur to make this blessing. What goes on under the holy tent he makes for himself? Only he knows for sure.

As a woman, I have not been interested in wearing, or making, a tallit. Some of the women in my Reform congregation wear them. I think of men like Joe Schuster and Jerry Siegel, two Jewish boys from Ohio who created the Superman character. Bob Kane, Will Eisner and Stan Lee were also Jewish guys who invented superheroes for the comics. Michael Chabon explored the connection between young Jewish men and comics superheroes in his book, The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay. Chabon posits that the evil-fighting golems were invented to perform tikkun olam (repairing the world). Perhaps the cape came from the tallit, and perhaps the tallit/cape worn by superheroes has invisible tzitzit (ritual fringes), like the fading marks on my father’s arm.

My rabbi (Bruce Elder, another Jewish boy from Ohio) recently asked me if I would lead a tallit/tzitzit workshop for the young students of our religious school at Congregation Hakafa in Illinois. As I learned to tie tzitzit and decorated a tallit as a model for the children, the strings tied their way around my heart. The kids got past their initial confusion about the mass of strings, and fell into a meditative calm as they knotted and twisted. Once the tzitzit were tied, they drew on their tallitot with fabric markers. I think the girls, in particular, seemed moved when they put on their tallit.

- Isabel, New Tallit, Judith Joseph

Marna Goldstein Brauner, a fiber artist from Milwaukee, Wisconsin, created a piece called Shawl that resembles a tallit katan, the vest-like garment worn by observant Jews under their clothes, which has tzitzit attached. It is lacy and delicate, and seems to beg the gender question about tzitzit.

- Shawl, Marna Goldstein Brauner

- Accumulations, mixed media, by Michelle Sales

Life is complicated. Some artists use threads to create a psychic armature, to map the interstices of our nervous system and the roots of our history. For Winfield, Illinois artist Michelle Sales, fiber is used as a sort of reverse archaeology. She layers and assembles memories, rather than stripping them away.

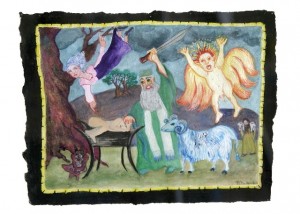

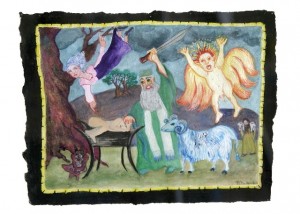

- Akedah, gouache, by Pat Allen

Sometimes the ties that bind us are more than psychological. The akedah, the binding of Isaac, is one of the most disturbing and provocative narratives in the Bible. Every time I hear it, I feel roiled up: as a parent, as a daughter. It is the not-icon; the epitome of what we must not do and be. Many artists have depicted the story throughout art history. It’s interesting to see what point in the narrative they choose to show: Isaac trudging along behind Abraham carrying a load of sticks; Abraham with his hand upon Isaac after tying him up; Isaac alone, terrified in his bindings; and most commonly, Abraham raising his hand to Isaac with an angel hovering nearby. I like this rendition by Oak Park, Illinois artist Pat Allen. I can hear the angel hollering, and that comforts me:

Suzanne Horwitz is primarily a sculptor. Her untitled drawing seems to explore the way matter holds together. And just as every artist experiences the wonder of creation, we all may feel a spiritual kinship with the Creator. Think of Job, Chapter 38:4-5:

ד ×ֵיפֹה הָיִיתָ, בְּיָסְדִי-×ָרֶץ;   הַגֵּד, ×Ö´×-יָדַעְתָּ ×‘Ö´×™× Ö¸×”. |

4 Where wast thou when I laid the foundations of the earth? Declare, if thou hast the understanding. |

×” מִי-×©×‚Ö¸× ×žÖ°×žÖ·×“Ö¼Ö¶×™×”Ö¸, ×›Ö¼Ö´×™ תֵדָע;   ×וֹ מִי-× Ö¸×˜Ö¸×” עָלֶיהָ קָּו. |

5 Who determined the measures thereof, if thou knowest? Or who stretched the line upon it? |

Her work is elemental, and it reminds me of the creation of the earth, moving from chaos into form.

- Untitled, graphite on paper, Suzanne Horwitz

Marco Brown’s paintings deal with the perceptions of our senses. A native of Malta, Marco is a linguist who has lived in Paris and Israel and presently lives in Berlin. Despite his talent with the intellectual constructs of words, his paintings are elemental, sensual , and instinctual.

, and instinctual.

- Shroud, oil on canvas, Marco Brown

We begin with a tie, the umbilical cord that connects us to our mother. We move through life, tied to each other by cords both tangible and invisible. And we end our lives enveloped in a shroud, a mass of threads, an echo of our earthly bonds and a promise of eternal moorings.

- In: Featured Artists|Inspiration

- Tags: Calligraphy, Feminist Art, Fiber Art, Midwest US

to The Ties That Bind

Berit Engen

October 3rd, 2013 at 10:47 pm

Thank you, Judith, for presenting these beautiful works in such a thoughtful and personal way – by giving of your own story you pull me in. By using your various ties you make it complete, yet you do not shut the viewer out for further explorations.